Magazines about Robert Wise, The Haunting or Shirley Jackson † Books about RW, The Haunting or SJ † Homage

Magazines & books about Robert Wise, The Haunting or Shirley Jackson

Magazines about Robert Wise, The Haunting or Shirley Jackson

'Famous Monsters of Filmland' (USA)

Mar., 1962 - No. 16

Issue: Mar., 1962 - No. 16

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: A 2-line mention of the film's cast.

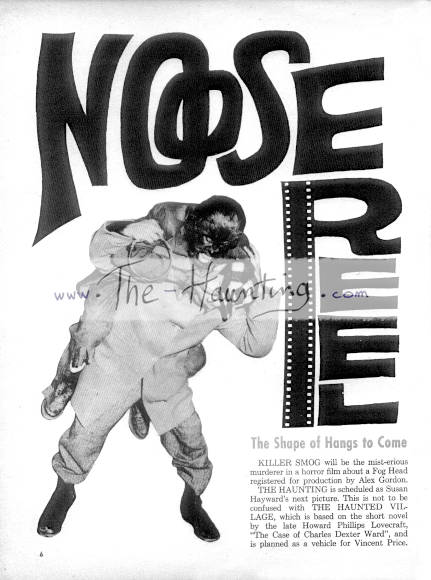

Page 6

The Haunting is scheduled as Susan Hayward's next picture.

Aug., 1963 - No. 24

Issue: Aug., 1963 - No. 24

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: One third of a column, very short report about the movie. A few words about the American actors chosen for the cast.

Page 13

"[...] All this in conjunction with the release of MGM's horror package, admitted tht it was a story of the supernatural with no ghosts to be seen but rather their spooky presence is felt. It will be sold as an adult terror picture. Picture cost $1,125,000. Prior to opening, to stir up interest there will be tours by experts on the supernatural, as well as seances ghost-to-ghost."

The Haunting is based on the novel "The Haunting of Hill House" by Shirley Jackson of The Lottery fame & has Russ Tamblyn & Julie Harris investigating the mystery of an old dark house (not to be confused with William's Castle).

Nov., 1972 - No. 94

Issue: Nov., 1972 - No. 94

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: Eleven full pages, all in black & white, with pictures, with 4 lines about The Haunting.

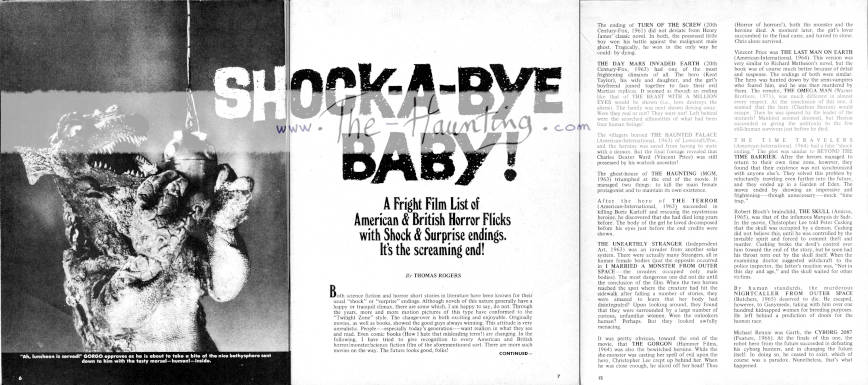

They feature an article titled "Shock-a-bye Baby! — A fright film list of American & British horror flicks with shock and surprise endings. It is the screaming end!", by Thomas Rogers.

Page 12

The ghost-house of The Haunting (MGM, 1963) triumphed at the end of the movie. It managed two things: to kill the main female protagonist and to maintain its own existence.

Jul.-Aug., 2015 - No. 280

Issue: Jul.-Aug., 2015 - No. 280

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: Four full pages, all in colour, with pictures.

They feature an article titled "Born bad: the legacy of Robert Wise's The Haunting", by Alexandra West.

Page 26, very short excerpt

As many have explored in academic writings, the haunted house or "traumatized house" represents a fear of the American ideal, offering the notion that the very goals prescribed to us are nothing more than a trap and something to be feared. THE HAUNTING presents Hill House, a house "born bad" that exploits the fears and psychologies of its inhabitants and our history. Hill House represents a holdover from the New World with Puritan ideologies, a clinging vestige to our collective past. As horror master Stephen King writes of THE HAUNTING in his treaties on tenor DANSE MACABRE: "The interesting thing lies in the fact that we never actually see whatever it is that haunts Hill House. Something is there, all right. Something knocks on the wall with a sound like a cannon fire... this same thing causes a door to bulge grotesquely inwards until it looks like a great convex bubble... but it is a door Wise elects never to open." Had Wise elected to open that door, so much of what haunts THE HAUNTING would have been taken away. We would see the man working the controls who would have clearly explained Nell's psychosis or the terrifying ghosts that are waiting around every turn in Hill House. THE HAUNTING never provides us with answers — only terrifying darkness.

'Kine Weekly' (UK)

Nov. 15, 1962 - Vol. 546, No. 2876

Issue: Nov. 15, 1962 - Vol. 546, No. 2876

Language: English

Country: UK

Content: One page (black & white) discussing various productions contains an article with picture about the movie.

Page 18

When a producer sets out to make a film of the supernatural the first thing he has to decide is what sort it is going to be — one with skeletons banging all over the place or the psychological type.

Producer-director Robert Wise has decided that there will be no materialisations in "The Haunting," now in production at MGM's Boreham Wood studios. Instead he is employing interesting camera and sound techniques to make the audience's blood tingle.

The picture stars Julie Harris, Claire Bloom. Richard Johnson and Russ Tamblyn. The story, scripted by Nelson Gidding from Shirley Jackson's novel "The Haunting of Hill House," is of four people who investigate the legend surrounding an old mansion.

Said Wise, "This is a modern ghost story. There are no clanking chains, no shrouds, no mummy's hands. It is a story of the supernatural with characters who remain ordinary human beings."

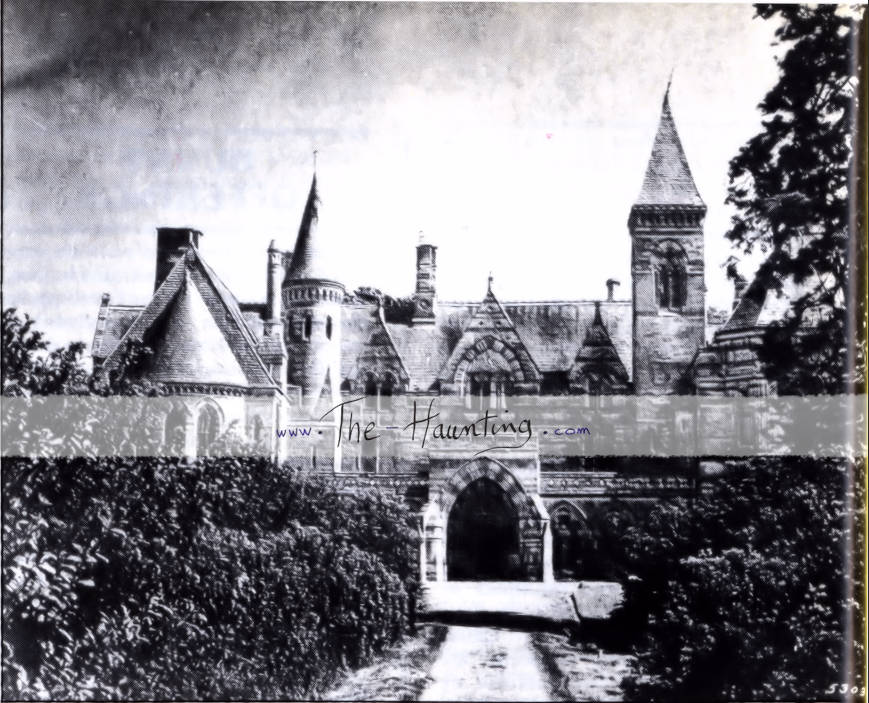

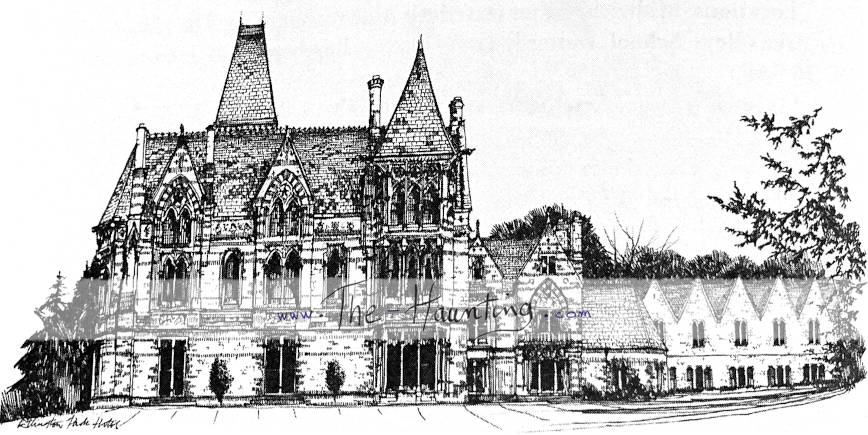

Camera-wise three methods were used to create creepiness. Locations at an 18th century manor house near Stratford-upon-Avon were shot on infra-red film. "It turns the sky almost black and very sinister," said Wise. "Another interesting characteristic of this film is that it photographs anything with chlorophyll in it, such as grass and trees, dead white." Also, in the camera equipment is a fog filter "to give a little haze." And for the first time a new 25-mm. Panavision lens is being used. It is, of course, a wide-angle lens, but that is not the main reason why it is being used. "When I told them I wanted to have this newly developed lens they said, 'But it has still got a little distortion,' " Wise related. "I said 'Great. Let me have it now, before you iron out the bugs! ' " Lighting cameraman Dave Boulton added enthusiastically, "It makes the house look just a little bit off, as if it was designed by a man who didn't like straight angles"

Sound-wise they have been enterprising, too. A sound crew under the leadership of dubbing editor Allan Sones was sent in the still of the night to another old house near St. Albans. After several nocturnal recording sessions Sones returned with a wonderful collection of sounds which were played back during rehearsals to stimulate the actors. And they will go on to the soundtrack, too.

These, then, are the modern techniques Wise has substituted for manifestations. He is determined to keep that skeleton firmly in the cupboard.

Connoisseurs will notice that this is a quite rare promotional picture. I own nearly a hundred of them but not this one.

Dec. 13, 1962 - Vol. 547, No. 2880

Issue: Dec. 13, 1962 - Vol. 547, No. 2880

Language: English

Country: UK

Content: One page (p109, black & white) fully describes the technical capabilities of the British MGM studio. See the page dedicated to the house for all details. Another page (p152, black & white) mentions the wrap up for Julie Harris.

Page 109, article by Maurice Foster (See the page dedicated to the house for all details.)

Page 152, production by Derek Todd

After completing her starring role in "The Haunting" at MGM's Boreham Wood studio on Christmas Eve, Julie Harris will fly to New-York for an important television commitment.

She is to play Eliza Doolittle in Bernard Shaw's "Pygmalion."

With Julie Harris in "The Haunting," produced and directed by Robert Wise for MGM, are Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson and Russ Tamblyn.

'Life' (USA)

Sep. 22, 1947

Issue: Sep. 22, 1947

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: Two full pages, then seven half pages, all in black & white, with pictures.

They feature an article titled "A Who's Who of English ghosts", by Noel F. Busch.

I mention this article because it was mentioned a decade later in the Oct. 28, 1957 article (see below).

You might be intrigued to read what was considered in 1947 the must-have kit for any well-appointed British ghost-hunter:

- Pair soft felt overshoes

- Steel measuring tape

- Screw eyes

- Lead seals and sealing tool

- White tape

- Toolbox and nails

- Hank of flax

- Small electric bells

- Dry batteries and switches

- Camera, films and flash bulbs

- Notebook

- Red, blue and black pencils

- Sketching block and case of drawing instruments

- Bandages

- Iodine

- Surgical adhesive tape

- Ball of string

- Stick of chalk

- Matches

- Electric torch and candle

- Bowl of mercury to detect tremors in room or passage (ghosts like passages)

- Cinematograph camera with electrical release

- Flask of brandy

The magazine was scanned by Google and is available here.

Jan. 11, 1954

Issue: Jan. 11, 1954

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: Two full pages, then seven half pages, all in black & white, with pictures.

They feature an article titled "A case for ESP, PK and PSI", by Aldous Huxley.

I mention this article because it was mentioned in the Mar. 17, 1958 article (see below).

The magazine was scanned by Google and is available here.

Oct. 28, 1957

Issue: Oct. 28, 1957

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: Twelve full colour pages, with pictures.

They feature a collection of short stories titled "Ghostly american legends", illustrated by pictures taken by Nina Leen.

According to a well-informed expert fan, Robert Wise had 6 copies of this magazine in his "The Haunting" file. They were probably used for ideas, inspiration or research.

The list of short stories of the article includes:

- A lovelorn lass

- The Baldwin lights

- An irascible old aunt

- A cry of death

- Ominous hoofbeats

- The bell witch of Tennessee

- A pirate's caretaker

- The welcome guest

- By moonlight burned

The magazine was scanned by Google and is available here.

Mar. 17, 1958

Issue: Mar. 17, 1958

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: One full page, then five half pages, all in black & white, with pictures.

They feature an article titled "House of flying objects", by Robert Wallace.

I mention this article because it describes a New-York based poltergeist case, investigated by both the police and by Dr. Rhine's assistant, Dr. J. Gaither Pratt.

The magazine was scanned by Google and is available here.

Aug. 30, 1963

Issue: Aug. 30, 1963

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: All black & white: one full page, three half-pages (2 with pictures, 1 with essay). They feature a short article titled "Great new scary film", followed by an essay by Dora Jane Hamblin titled "Go on, frighten us to death, we love it!"

Child ages in 20 seconds. Great new scary film. [Full text]

Everybody who has brooded over the way life speeds — and who hasn't? — will get goose-pimples from the sequence here in a wonderfully scary movie called "The Haunting", as convincing and chilling as "The turn of the screw", based on Shirley Jackson's novel "The Haunting of Hill House", it begins as a little girl goes to live in an isolated monstrosity of a house built by her father. As the family carriage approaches the house, the horses rear in terror at some aura of evil, and the girl's mother is killed. The child goes to live in the house's nursery and there grows old in a 20-second photographic trick, and dies crying out futilely for help. The terror mounts as a professor brings an odd pair of researchers to help him check the house for supernatural influences. One is a woman with extrasensory perception, the other is near-hysteric. The women, brilliantly acted by Julie Harris and Claire Bloom, find they can't sleep nights, in that house. Audiences will find they can't sleep afterwards either.

Kept awake by hideous noises, two researchers, Claire Bloom and Julie Harris, are too scared to scream.

Terror becomes hysterical laughter as the professor, who hasn't heard a thing, asks the girls what happened.

Setting for shudders in "The Haunting" is a real haunted house — an 18th century manor in England — chosen by producer-director Robert Wise. Legend says a ghost stalks the turrets — the ghost of a girl who threw herself from a balcony one Friday because she couldn't marry her lover. "We didn't film on Fridays," says Wise.

Go on, frighten us to death, we love it! [Excerpt]

[...] The truth is, most people love to be scared. Some friends of mine went to see "The Haunting", taking along their purses and their white gloves, their glasses and their cigarets. During the course of the movie they jumped in and out of their seats and each other's laps so many times out of sheer terror that it took 15 minutes after the lights went on to sort their belongings, all of which had landed in a heap on the floor and had, in fact, rather impeded their own movements as they tried to crawl under the seats. When they all had their own gloves and glasses back, they judged the film "wonderful". [...]

The magazine was scanned by Google and is available here.

'Positif' (France)

Dec. 1963, No. 57

Issue: Dec. 1963, No. 57

Language: French

Country: France

Content: Half a page, in black & white. The movie is reviewed by Robert Benayoun.

I can't show you the inside of the magazine without destroying the binding: it prevents from scanning the magazine flat.

Page 46 (Original French)

Pourquoi Robert Wise, après une comédie musicale trépidante, s'est-il perdu dans le film d'horreur ? demandera l'historien en peine d'étiquettes. Question que le laisserai délibérément sans réponse, puisqu'aussi bien "The Haunting" est un triomphe de Wise sur l'Hitchcock de "Psycho", pour ne prendre qu'un seul exemple, et échappe du même tout à toutes les catégories un peu hâtives.

C'est plus qu'autre chose un film sur la peur, la peur irrationnelle, panique et presque obscène, que rien ne rationalise. Dans cette maison hantée que visitent deux médiums et un parapsychologue éminent, rien sans doute n'existe, que les fantômes de notre subconscient. Mais si la peur est transférable, si elle s'agglutine autour du moindre noyau d'ombre et de refoulement, elle peut assumer les proportions d'un cataclysme hurlant, d'une régression vers l'inhumain. Robert Wise fuit, ici, toute explication, mais il déchaine sur nous un sabbat immatériel, qui est l'expérience la plus terrifiante du genre. Car si aucun monstre ne nous apparaît, si nul crime n'est commis, ce n'est pas au profit d'une sobriété, d'une discrétion ascétiques, visant à la stéréotypie. Non, l'hystérie, la démesure bouleversent notre attente, et nous enlèvent tout contrôle critique. La machinerie hitchcockienne, à base de petites observations, de gradations subtiles et de calculs savants est rejetée en faveur d'un mouvement lyrique tortueux et irrésistible. L'art de Wise éclate d'autant mieux qu'il défie le sujet, domine jusqu'à l'interprétation hors pair de Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson. Je ne connais rien (à l'exception peut-être des "Innocents") qui se rapproche autant de la magie.

Page 46 (English translation)

Why did Robert Wise, after a hectic musical, get lost in the horror film? asks the historian in need of labels. A question that he would deliberately leave unanswered, since "The Haunting" is a triumph of Wise over the Hitchcock of "Psycho", to take just one example, and escapes all the somewhat hasty categories.

It is more than anything else a film about fear, irrational, panicky and almost obscene fear, which nothing rationalises. In this haunted house visited by two mediums and an eminent parapsychologist, nothing undoubtedly exists but the ghosts of our subconscious. But if fear is transferable, if it agglutinates around the slightest nucleus of shadow and repression, it can assume the proportions of a screaming cataclysm, of a regression towards the inhuman. Here Robert Wise avoids any explanation, but he unleashes upon us an immaterial Sabbath, which is the most terrifying experience of the genre. For if no monster appears to us, if no crime is committed, it is not for the benefit of ascetic sobriety, ascetic discretion, aiming at stereotyping. No, hysteria and excessiveness upset our expectations and take away all critical control. The Hitchcockian machinery, based on small observations, subtle gradations and learned calculations, is rejected in favour of a tortuous and irresistible lyrical movement. Wise's art explodes all the more as it defies the subject, dominating even to the unparalleled interpretations of Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson. I don't know anything (with the possible exception of the "Innocents") that comes so close to magic.

'Les cahiers du cinéma' (France)

Dec. 1963-Jan. 1964, No. 150-151

Issue: Dec. 1963-Jan. 1964, No. 150-151

Language: French

Country: France

Content: Two full pages, in black & white. Robert Wise gives an update about his forthcoming projects ("The sound of Music" & "The sand peebles"). He briefly mentions "The Haunting" as his last movie.

Apr. 1964, No. 154

Issue: Apr. 1964, No. 154

Language: French

Country: France

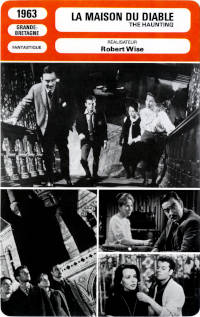

Content: Listing of movies released in Paris, France between Feb. 12 - March 10, 1964. Four lines about "The Haunting".

Page 77 (Original French)

The Haunting (La Maison du Diable), film en Scope de Robert Wise, avec Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, Russ Tamblyn. — Un château hanté ; si l'on voulait vraiment nous faire peur, il fallait plus nettement choisir entre la convention (mais le script essaie d'y échapper) ou la rigueur (que la mise en scène fuit obstinément).

Page 77 (English translation)

The Haunting (La Maison du Diable, literally The Devil's House), film in Scope by Robert Wise, with Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, Russ Tamblyn. — A haunted castle; if they really wanted to scare us, they had to choose more clearly between convention (but the script tries to escape it) or rigour (which the director stubbornly avoids).

May 1964, No. 155

Issue: May 1964, No. 155

Language: French

Country: France

Content: Two pages and a half, in black & white, including one picture. They feature an article by Michel Mardore titled "Les folles du logis", which is a double review: "The Haunting" & "The Fall of the House of Usher"

Remark: You might be puzzled by the English translation, because it makes no sense. Don't worry. It is because the original in French also makes no sense and I strongly disagree with almost all of it.

Page 50 to 52 (Original French), excerpt:

The Haunting (La Maison du Diable), film américain en Panavision de Robert Wise. Scénario : Nelson Gigging, d'après le roman de Shirley Jackson. Images : David Boulton. Musique : Humphrey Searle. Montage : Ernest Walter. Interprétation : Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, Russ Tamblyn, Lois Maxwell, Rosalie Crutchley, Fay Compton, Valentine Dyall. Production : Robert Wise, Argyle Enterprises. 1963. Distribution : M.G.M.

L'argument qui conduit à réunir ces films, de conception assez différentes, dans la même analyse, pourra sembler superficiel : la clé, esthétique et morale, des deux entreprises est l'idée de capture, d'une possession réciproque de l'inanimé et du vivant. Comme, dans les deux cas, une maison (avec toute la force psychanalytique attachée à ce symbole) est le lieu où la fusion entre l'être et l'objet s'opère, le décor devenu agent et sujet, le rapprochement s'impose : il aboutit à un double constat de faillite.

L'impression de vie autonome et d'omnipotence maléfique, dont ces demeures devraient nous convaincre, n'est jamais véritablement communiquée au spectateur. Pour The Haunting, la gravité de l'échec est plus évidente, Robert Wise ne cachant pas son ambition. Alors qu'il annonce comme un postulat, et répète durant tout le film, que Hill House est vivante, jamais ses images ne parviennent à nous révéler cette existence supranormale et ce pouvoir de la matière filmée. D'autre part, les temps de repos ne trahissent aucun mystère latent, et la réalisation renchérit sur l'insignifiance et l'inexpressivité des êtres et des choses ; d'autre part, les temps forts, où se manifeste la puissance occulte, servent de prétexte à un festival technique d'une pauvreté qui inspire davantage de tristesse que d'effroi. Toute la terreur de l'inconnu tiendrait donc dans ces travelings, ces contreplongées naïves, ces distorsions caligaresques de l'image (par utilisation, pour la première fois à notre connaissance, d'objectifs à court foyer couplés avec les anamorphoseurs du Scope), sans parler des cris d'épouvante que poussent les personnages, ni du tonitruant appoint musical ? Enfin, lorsque le bric-à-brac visuel ne peut évoquer, même de façon caricarturale, un sentiment trop subtil, on recourt au dialogue et au commentaire : les personnages occupent leur temps libre à dire : "Il se passe telle et telle chose ... Je ressens ceci et cela ..." A défaut de ces explications, de ces tentatives de suggestion, nous serions bien incapables de détecter une ombre d'activité ou de simple influence émanant de la fameuse maison. Sans accabler Robert Wise, car la cinématographie de l'invisible est une gageure, on doit rappeler que d'autres cinéastes ont jadis relevé le même défit — à commencer par Murnau et Dreyer — et ne se sont pas mal tirés de l'épreuve. Le véritable problème de la "métaphysique" au cinéma tient dans ce genre de pari, et celui qui joue avoue son incapacité de créateur.

Il est vrai qu'à partir de cet escamotage du fantastique, on infère à loisir une ambigüité troublante des intentions. Wise ne croirait guère aux maisons hantées : pour lui, l'angoisse ressentie au contact de phénomènes étrangers et inexpliqués cristalliserait nos obsessions et nos névroses, jusqu'à l'exécution des événements désirés en secret par notre subconscient (ici, Julie Harris meurt pour satisfaire le voeu d'autopunition né d'un complexe de culpabilité). L'idée n'est pas nouvelle, et la science-fiction a déjà envisagé l'utilisation de véritables champs de forces magnétiques issus de notre activité mentale. Cette arrière-pensée des auteurs justifierait l'attitude aberrante de ce psychiatre, qui introduit comme médiums, dans cette maison inquiétante, deux femmes hyperémotives et douées d'une très forte polarisation sexuelle, ce qui ne constitue pas une fameuse garantie d'exactitude scientifique, mais promet une extrême concentration de potentiel psychique. A la limite, avec de tels sujets, les thèses physiques avancées par les spécialistes de la parapsychologie suffiraient à la compréhension des rares phénomènes "anormaux" décrits au cours du film. Quand on sait que le personnage incarné par Julie Harris a provoqué, lors de sa puberté, des faits de "poltergeist" absolument classiques, il ne faut pas s'étonner des bruits violents et des mouvements de boutons de portes qui se produisent en sa présence : le réveil brutal de sa sexualité, amorcé par la disparition de sa mère, est accru par son penchant pour le psychiatre et par son attitude d'attraction-répulsion envers la lesbienne. Exemple caractéristique : après la déception que cause à Julie Harris l'arrivée de la femme du psychiatre, elle se rapproche de Claire Bloom. Aussitôt commence la scène terrifiante où les panneaux de la porte du salon cèdent presque sous la pression d'une "masse" mystérieuse. Julie Harris, pas plus que les autres personnages, ne soupçonne que loin d'attirer à elle cette force, elle en est au contraire l'émettrice, la source vivante.

Dès lors, à quoi rime toute cette mise en scène sur le thème de la maison "animale et perverse" ? Ce genre de phénomène, dont est victime la jeune femme, peut se produire dans le plus riant cottage, sans aucune emprise extérieure, puisqu'il dépend de la personne et non du décor. Wise invoque tout un background correspondant au film fantastique, dont nous ne trouvons pas de trace dans sa réalisation. Pourquoi ce cadre relevant du romantisme noir, et pourquoi les suicides et l'architecture décentrée par un misanthrope imbu de puritanisme morbide ? Le contexte et le traitement ne cessent de jouer sur ces contradictions. Mais une partie sur deux tableaux ne prouve pas toujours une habileté extrême : elle dénote plutôt faiblesse ou confusion de pensée. Affolé par les outrances du fantastique, indécis en face des thèses de la parapsychologie, Wise a cherché un compromis absurde, en espérant que chacun y trouverait son compte. Mauvais calcul : on ne transforme pas un manoir hanté en auberge espagnole. Les tenants du réalisme, comme ceux du fantastique (parfois les mêmes, et cela donne le réalisme fantastique, tellement à la mode), risquent de n'y découvrir qu'aliments à critiques.

Un sujet peu commun, d'ordinaire esquivé par le cinéma (surtout par le cinéma dit fantastique), est donc simplement effleuré, faute de compétence, d'information, et peut-être de courage. Reste un scénario agrémenté de trouvailles littéraires remarquables : nous n'oublierons pas (au hasard) la scène de la main serrée par ..., ni le point glacial lovecraftien, ni la bibliothèque assassine, et quelques autres délicieux frissons.

Page 50 to 52 (English translation), excerpt:

The Haunting (La Maison du Diable), an American film in Panavision by Robert Wise. Screenplay: Nelson Gigging, based on the novel by Shirley Jackson. Pictures: David Boulton. Music: Humphrey Searle. Editing: Ernest Walter. Cast: Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, Russ Tamblyn, Lois Maxwell, Rosalie Crutchley, Fay Compton, Valentine Dyall. Production: Robert Wise, Argyle Enterprises. 1963. Distribution: M.G.M.

The argument that leads to bring together these films, of quite different conception, in the same analysis, may seem superficial: the key, aesthetic and moral, of both enterprises is the idea of capture, of a reciprocal possession of the inanimate and the living. Since, in both cases, a house (with all the psychoanalytical force attached to this symbol) is the place where the fusion between being and object takes place, the décor becoming agent and subject, the rapprochement is essential: it leads to a double acknowledgement of bankruptcy.

The impression of independent living and evil omnipotence, which these homes should convince us of, is never really communicated to the viewer. For The Haunting, the seriousness of the failure is more obvious, Robert Wise making no secret of his ambition. While he announces as a postulate, and repeats throughout the film, that Hill House is alive, his images never manage to reveal to us this supranormal existence and this power of the filmed material. On the other hand, the times of rest do not betray any latent mystery, and the filming adds to the insignificance and inexpressiveness of beings and things; on the other hand, the high points, where the occult power manifests itself, serve as a pretext for a technical festival of a poverty that inspires more sadness than dread. All the terror of the unknown would thus fit into these travelings, these naive counter-dips, these caligresque distortions of the image (by using, for the first time to our knowledge, short focus lenses coupled with the anamorphic lenses of the Scope), not to mention the cries of terror that the characters utter, nor the thunderous musical accompaniment? Finally, when the visual bric-a-brac cannot evoke, even in a caricatured way, a feeling that is too subtle, we resort to dialogue and commentary: the characters spend their free time saying: "Such and such a thing is happening ...". I feel this and that ...". Without these explanations, these attempts at suggestion, we would be quite incapable of detecting a shadow of activity or simple influence emanating from the famous house. Without overwhelming Robert Wise, because the cinematography of the invisible is a challenge, we must remember that other filmmakers have taken up the same challenge in the past — starting with Murnau and Dreyer — and did not fare badly. The real problem of "metaphysics" in cinema lies in this kind of gamble, and the gambler admits his inability to create.

It is true that from this evasion of the fantastic, one can infer at leisure a disturbing ambiguity of intentions. Wise would hardly believe in haunted houses: for him, the anguish felt in contact with strange and unexplained phenomena would crystallize our obsessions and neuroses, until the execution of the events desired in secret by our subconscious (here, Julie Harris dies to satisfy the vow of self-punishment born of a guilt complex). The idea is not new, and science fiction has already envisaged the use of real magnetic force fields resulting from our mental activity. This ulterior motive of the authors would justify the aberrant attitude of this psychiatrist, who introduces as mediums, in this worrying house, two hyper-emotional women endowed with a very strong sexual polarisation, which is not a famous guarantee of scientific accuracy, but promises an extreme concentration of psychic potential. At the limit, with such subjects, the physical theses put forward by the specialists of parapsychology would suffice to understand the rare "abnormal" phenomena described in the course of the film. When we know that the character played by Julie Harris provoked, during her puberty, absolutely classic "poltergeist" acts, we should not be surprised by the violent noises and the movements of door knobs that occur in her presence: the brutal awakening of her sexuality, initiated by the disappearance of her mother, is increased by her penchant for psychiatry and by her attraction-repulsion attitude towards the lesbian. A typical example: after Julie Harris' disappointment with the psychiatrist's wife's arrival, she moves closer to Claire Bloom. Immediately begins the terrifying scene where the panels of the living room door almost give way under the pressure of a mysterious "mass". Julie Harris, like the other characters, does not suspect that far from attracting this force to her, she is, on the contrary, the emitter, the living source of it.

So what is the point of all this staging on the theme of the "animal and perverse" house? This kind of phenomenon, of which the young woman is a victim, can occur in the most laughable cottage, without any outside influence, since it depends on the person and not on the decor. Wise invokes a whole background corresponding to the fantasy film, of which we find no trace in his making. Why this setting of dark romanticism, and why the suicides and off-centre architecture by a misanthrope imbued with morbid puritanism? The context and the treatment keep playing on these contradictions. But one part in two paintings does not always prove extreme skill: it rather denotes weakness or confusion of thought. Distraught by the excesses of the fantastic, indecisive in the face of the theses of parapsychology, Wise sought an absurd compromise, hoping that everyone would find something to their liking. Miscalculation: a haunted mansion is not transformed into a Spanish inn. The proponents of realism, like those of fantasy (sometimes the same ones, and that gives fantastic realism, so fashionable), risk discovering only food for criticism.

An uncommon subject, usually avoided by cinema (especially by so-called fantastic cinema), is therefore simply brushed aside, due to a lack of skill, information and perhaps courage. What remains is a scenario embellished with remarkable literary discoveries: we will not forget (at random) the scene of the hand shaking by ..., nor the icy Lóvecraftian point, nor the murdering library, and a few other delicious shivers.

'Monthly Film Bulletin', published by the British Film Institute (UK)

Jan. 1964, Vol. 31, No. 360

Publisher: The British Film Institute

Issue: Jan. 1964, Vol. 31, No. 360

Language: English

Country: UK

Content: A review. Spreading over a little more than just a column in the magazine, in black & white. The movie is reviewed by T.M..

Page 4 to 5

Hill House, near Boston, has stood empty for eighty years. Legend has it that its tyrannical owner, Hugh Crain, caused the death of two wives; that his daughter Abigail grew up in the house, to die as an old woman when her companion ignored her call for help; and that the companion died falling from a spiral staircase. Dr. Richard Markway, an anthropologist, determines to investigate stories that the house is haunted. He is accompanied by Luke Sannerson, sceptical nephew of the present owner, and two women selected to help in his experiments: Eleanor, a nervous spinster who devoted her life to her sick mother, and was attacked by poltergeists after her mother's death; and Theo, a self-possessed young businesswoman with remarkable powers of extra-sensory perception. As soon as they arrive both women — Eleanor in particular — are assailed by threatening noises. Markway discovers that Eleanor feels guilty about her mother because, like Abigail's companion, she failed to answer a call for help. He tries unsuccessfully to persuade her to leave. Tension grows when Theo is attracted to Eleanor, but Eleanor is more interested in Markway. The strange disturbances continue, and seem to centre on the nursery where Abigail lived and died. Markway's domineering wife, Grace, arrives unexpectedly, and determines to sleep in the nursery. That night, after a particularly violent bout of noises, Grace disappears. While searching for her, Eleanor, under some strange impulsion, climbs the rickety spiral staircase. Thinking that she sees Grace's face at a skylight, Eleanor almost falls, but Markway rescues her, and decides that it is too dangerous for her to stay any longer. Distressed, Eleanor suddenly drives off alone. A ghostly figure flits across the driveway, and the car, apparently out of control, crashes. Eleanor is killed. The ghostly apparition turns out to be Grace, scared by the noises and lost in the warren of corridors.

Nearly twenty years ago, Robert Wise made his directorial debut under Val Lewton's expert guidance with The Curse of the Cat People, an attractively atmospheric tale of the ghostly world evoked by a lonely child in a darkly sinister mansion. The Haunting tries hard to follow Lewton's admirable principle that things suggested are more effective than things actually seen, and apart from Grace's two rather risible appearances as ghastly face pressed to skylight and as wraith in the park, the supernatural manifestations take place off-screen. The mysterious noises themselves are quite pleasingly chilling — though at one point unfortunately reminiscent of a flushing toilet — but Wise's camera is so determinedly zooming in and out to make sure one knows that the girls are scared and that the noises are just outside the door, and the music is so equally determined to let one know that there is something to be scared about, that all subtlety is banished. In one scene, for instance, the noises start and the terrified Eleanor clutches Theo's hand, only to find when they stop that Theo is asleep at the other side of the room. Wise plays the whole scene on a close-up of Eleanor, cutting back triumphantly at the end to reveal the horror — her empty hand; but because the camera ostentatiously avoids including Theo, it is child's play to deduce that she is not holding Eleanor's hand, and the scene goes for nothing (Lewton, almost certainly, would have suggested playing the scene, much more evocatively, on a held shot of Theo asleep, with Eleanor's voice off-screen begging her to hold on). Throughout, the script makes far too much play with old friends like the forbiddingly oracular housekeeper (Rosalie Crutchley à la Judith Anderson's Mrs. Danvers), slamming doors, the crumbling spiral staircase. An occasional interesting hint is thrown out, but never really taken up: the suggestion, for instance, that because the architect had deliberately avoided right angles, the house adds up to "one monstrous distortion". Wise tackles this tempting lead simply by shooting some scenes with a distorting lens, with the result that the walls are so concave that one appears to be in a fairground Hall of Mirrors. Julie Harris, all fluttering eyelids and quivering sensibility, spends her time muttering vague lines like "The House Wants Me!", but Claire Bloom gives a sharply intelligent performance as the Lesbian Theo, who is doubly tormented as her special powers of perception enable her to read all the emotionally repressed Eleanor's feelings. Richard Johnson is adequate; Russ Tamblyn, presumably included in the cast to crack a few sceptical jokes, does so.

'ABC Film Review' (UK)

Jan. 1964, Vol. 14, No. 1

Issue: Jan. 1964, Vol. 14, No. 1

Language: English

Country: UK

Content: A full page advertisement for the movie, plus one double page, in black & white. The movie is reviewed by Elizabeth Hardie.

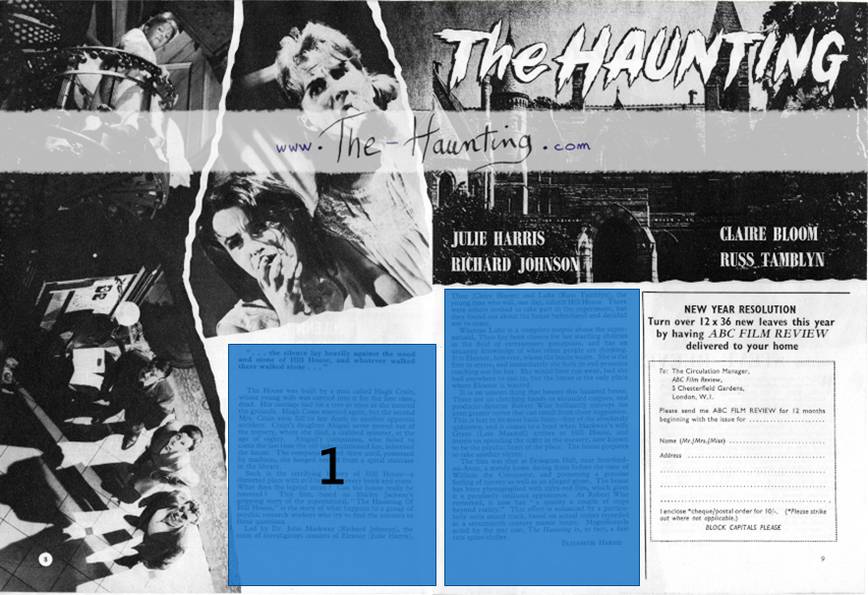

Page 8 to 9

The House was built by a man called Hugh Crain, whose young wife was carried into it for the first time, dead. Her carriage had hit a tree as soon as she entered the grounds. Hugh Crain married again, but the second Mrs. Crain soon fell to her death in another apparent accident. Crain's daughter Abigail never moved out of the nursery, where she died, a crabbed spinster, at the age of eighty. Abigail's companion, who failed to come the last time the old lady summoned her, inherited the house. The companion lived there until, possessed by madness, she hanged herself from a spiral staircase in the library.

Such is the terrifying history of Hill House — a distorted place with evil built into every brick and stone. What does the legend mean? Can the house really be haunted? This film, based on Shirley Jackson's gripping story of the supernatural, "The Haunting Of Hill House," is the story of what happens to a group of psychic research workers who try to find the answers to these questions.

Led by Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson), the team of investigators consists of Eleanor (Julie Harris), Theo (Claire Bloom) and Luke (Russ Tamblyn), the young man who will, one day, inherit Hill House. There were others invited to take part in the experiment, but they found out about the house beforehand and decided not to come.

Whereas Luke is a complete sceptic about the supernatural, Theo has been chosen for her startling abilities in the field of extrasensory perception, and has an uncanny knowledge of what other people are thinking. It is Eleanor, however, whom the house wants. She is the first to arrive, and immediately she feels its evil presence reaching out for her. She would have run away, had she had anywhere to run to, but the house is the only place where Eleanor is wanted.

It is an unseen thing that haunts this haunted house. There are no clutching hands or shrouded corpses, and producer-director Robert Wise brilliantly conveys the even greater terror that can result from sheer suggestion. This is fear in its most basic form — fear of the absolutely unknown, and it comes to a head when Markway's wife Grace (Lois Maxwell) arrives at Hill House, and insists on spending the night in the nursery, now known to be the psychic heart of the place. The house prepares to take another victim...

The film was shot at Ettington Hall, near Stratford-on-Avon, a stately home dating from before the time of William the Conqueror, and possessing a genuine feeling of history as well as an alleged ghost. The house has been photographed with infra-red film, which gives it a peculiarly ominous appearance. As Robert Wise remarked, it now has "a quality a couple of steps beyond reality." This effect is enhanced by a particularly eerie sound track, based on actual noises recorded in a seventeenth century manor house. Magnificently acted by the star cast, The Haunting is, in fact, a first-rate spine-chiller.

'Cinéma 64' (France)

Apr. 1964, No. 85

Issue: Apr. 1964, No. 85

Language: French

Country: France

Content: One page, in black & white. The movie is reviewed by Yves Boisset.

I can't show you the inside of the magazine without destroying the binding: it prevents from scanning the magazine flat.

Page 122 (Original French), excerpt:

L'une des plus désastreuses conséquences de la crise terrible que vient de traverser le cinéma américain fut la suspension presque radicale des productions de série B (westerns, thrillers, films d'action, films de guerre et films de terreur, pour l'essentiel) au profit de grosses machines prétentieuses, laborieusement fabriquées avec beaucoup de milliards et très peu d'idées. Le succès triomphal d'un film simplement intéressant comme Johnny Cool provient certainement en grande partie de cette nostalgie du public pour les séries B d'antan. Il semble pourtant que la production ait repris d'une façon normale à Hollywood, et il est assez significatif qu'un réalisateur aussi important que Robert Wise ait eu envie de traiter un genre mineur, comme le film de terreur, en réalisant La Maison du Diable.

Renouant avec un genre qu'il avait déjà traité avec brio à ses débuts dans des films comme Curse of the Cat People ou The Body Snatchers, Wise a visiblement voulu faire de The Haunting un film exemplaire. Un professeur de philosophie passionné de surnaturel a réuni dans une maison que l'on dit hantée deux jeunes femmes névrosées, qui furent déjà auparavant témoins de manifestations de l'au-delà, et le très jeune propriétaire de la maison, qui ne croit pas plus en le diable qu'en Dieu. Pourtant, dès l'arrivée des quatre volontaires dans la maison maudite, d'étranges manifestations se produisent : des coups sourds ébranlent les murs, des ricanements et des gémissements épouvantables retentissent dans les longs couloirs déserts, et des présences indicibles rôdent autour des deux femmes dès qu'elles se trouvent seules. La plus fragile d'entre elles trouvera la mort au cours d'un étrange accident, qui survient exactement à l'endroit où s'était tuée près d'un siècle auparavant la première propriétaire. Terrifiés, les trois survivants abandonneront leur dangereuse expérience et quitteront la maison qui gardera inviolés ses horribles secrets.

Avec un sujet de ce genre, l'équilibre est subtil et le choix difficile entre l'admission pure et simple des phénomènes surnaturels (Terence Fisher), et la justification logique d'événements tout à fait irrationnels (Castle ou tradition Val Lewton). Or le récit de Wise hésite constamment entre ces deux partis-pris. Et si certaines scènes constituent de véritables morceaux d'anthologie du cinéma fantastique (les premières manifestations surnaturelles dans la maison endormie, l'ascension de l'escalier en spirale), le manque de rigueur du scénario réduit considérablement l'adhésion du spectateur. D'autre part, les quatre personnages pour lesquels on est censé frissonner sont si peu attachants et si peu vraisemblables, que l'on se désintéresse assez vite de leur sort : Julie Harris est, en particulier, si exaspérante dans son emploi habituel de vierge mythomane et racornie que l'on se prend vite à espérer sa défloration immédiate par quelque audacieux succube. Seule, Claire Bloom, de plus en plus troublante depuis qu'elle travaille à Hollywood, impose avec beaucoup d'autorité son personnage de lesbienne névrosée en prise directe avec les manifestations de l'au-delà.

De toute évidence, Robert Wise est un très grand metteur en scène, sinon un auteur. Il y a dans son film des moments qui sont parmi les plus grands moments de l'histoire du cinéma fantastique. Mais il manque peut-être à ce film trop bien fait une vertu essentielle, c'est-à-dire au-delà des intentions dialectiques, le lyrisme de la sincérité.

Page 122 (English translation), excerpt:

One of the most disastrous consequences of the terrible crisis that American cinema has just gone through was the almost radical suspension of B-series productions (westerns, thrillers, action films, war films and terror films, for the most part) in favour of big pretentious machines, laboriously manufactured with many billions and very few ideas. The triumphant success of a simply interesting film like Johnny Cool certainly stems in large part from this nostalgia of audiences for the B-series of yesteryear. It seems, however, that production has resumed in a normal way in Hollywood, and it is quite significant that a director as important as Robert Wise wanted to deal with a minor genre, such as the terror film, by directing La Maison du Diable [The Haunting].

Returning to a genre that he had already dealt with brilliantly in his early days in films such as Curse of the Cat People or The Body Snatchers, Wise obviously wanted to make The Haunting an exemplary film. A philosophy professor with a passion for the supernatural has brought together two neurotic young women, who had already witnessed manifestations of the afterlife before, and the very young owner of the house, who believes no more in the devil than in God, in a house that is said to be haunted. However, as soon as the four volunteers arrive in the cursed house, strange manifestations occur: muffled blows shake the walls, appalling sneers and groans resound in the long deserted corridors, and unspeakable presences lurk around the two women as soon as they are alone. The most fragile of them will die in a strange accident, which occurs exactly where the first owner was killed almost a century ago. Terrified, the three survivors will abandon their dangerous experience and leave the house, which will keep its horrible secrets safe.

With a subject of this kind, the balance is subtle and the choice is difficult between outright admission of supernatural phenomena (Terence Fisher), and the logical justification of completely irrational events (Castle or the Val Lewton tradition). Yet Wise's narrative is constantly wavering between these two sides. And while some scenes are veritable pieces of fantasy cinema anthology (the first supernatural manifestations in the sleeping house, the ascent of the spiral staircase), the lack of rigour in the script considerably reduces the viewer's adherence. On the other hand, the four characters for whom one is supposed to shudder are so unlovable and unlikely that one quickly loses interest in their fate: Julie Harris, in particular, is so exasperating in her usual job as a shrivelled, mythomaniacal virgin that one quickly begins to hope for her immediate defloration by some daring succubus. Alone, Claire Bloom, more and more disturbing since she has been working in Hollywood, imposes with great authority her character of neurotic lesbian in direct contact with the manifestations of the afterlife.

Clearly, Robert Wise is a very great director, if not an author. There are moments in his film that are among the greatest moments in the history of fantasy cinema. But perhaps this film, too well made, lacks an essential virtue, that is to say, beyond dialectical intentions, the lyricism of sincerity.

'Midi-Minuit Fantastique' (France)

Jul. 1964, No. 9

Issue: Jul. 1964, No. 9

Language: French

Country: France

Content: Three pages, in black & white, with French artwork. The movie is reviewed by Michel Caen.

I can't show you the inside of the magazine without destroying the binding: it prevents from scanning the magazine flat.

Page 116 to 118 (Original French), excerpt:

La renommée de Wise, pourtant confirmée par le succès de "West Side Story", et la grande mode que connaissent actuellement les esprits frappeurs et la parapsychologie n'empêchèrent pas "La Maison du Diable" d'effectuer une sortie peu remarquée, pour le moins, et de connaître une exclusivité très brève, rivalisant ainsi avec "La Chute de la Maison Usher" qui, malgré sa récente reprise au Studio Parnasse, fut victime d'une exploitation particulièrement peu efficace.

Malgré les apparences, "The Haunting" ne met en scène ni un véritable cas de maison hantée — au sens traditionnel du terme — ni une de ces escroqueries destinées à effrayer d'éventuels locataires comme le cinéma nous en proposa souvent, puisque même l'admirable "Mark Of The Vampire" se soumettait à ces conventions rationalistes. Hill House, sinistre demeure de la Nouvelle Angleterre possède une réputation peu enviable. Depuis près de cent ans la "malédiction" pèse sur cette horrible bâtisse dont l'aspect seul évoque la mort et la lente décomposition. La femme pour qui cette maison fut construite, ne l'habitat jamais et, dans le parc, un arbre géant conserve encore une troublante cicatrice, vestige de l'accident qui causa la mort de la jeune épouse. Depuis les morts se sont succédées, toutes insolites sinon suspectes et la légende locale assure que les "victimes" continuent à peupler Hill House. Jusque-là, si j'ose dire, rien que de très naturel. L'affaire se complique lorsque le Dr. Markway, anthropologiste éminent et psychologue de surcroît, décide de louer la maison pour l'été afin de s'y livrer à quelques expériences que ne renieraient pas Rhine et ses collègues. Il s'entoure de médiums — au sens étymologique — c'est-à-dire d'êtres Hypersensibles ou en pleine crise de mutation organique ou psychique qui doivent permettre aux phénomènes surnaturels de se manifester. Le Dr. Markway fait preuve d'une remarquable honnêteté scientifique puisqu'il se borne ici à enregistrer, sans aucune interprétation, l'occurrence et la fréquence des manifestations inexpliquées.

Dans "La Maison du Diable" nous ne connaitrons jamais l’explication ultime. Les phénomènes qui furent indubitablement enregistrés resteront inaccessibles à toute appréhension rationnelle. Il ne s'agit pas, bien sûr, de fantômes élégamment vêtus de suaires immaculés mais simplement de bruits inexplicables, d'objets déplacés sans cause apparente et surtout de l'impression résolument atroce que la Maison désire garder en elle une présence vivante. En l'occurrence l'hypersensible Eleanor, désespérément attirée par cette extraordinaire demeure où les hautes fenêtres semblent autant d'orbites vides, de regards morts fascinants leur proie comme certains octopodes, dit-on, hypnotisent leurs victimes.

L'autre femme, Théodora, ravissante brune apparemment aussi clairvoyante et télépathe que fidèle au culte de Sapho se laissera finalement gagner par la terreur panique d'Eleanor. Le cinéma nous offre alors une des plus pures séquences d'épouvante lorsque les deux femmes réfugiées sur le même lit entendent la maison résonner de gigantesques coups de boutoirs et voient la porte de leur chambre ployer, se gonfler, se distendre littéralement sous la pression monstrueuse de la force qui erre dans le couloir, que nous ne verrons jamais et qui nous attire comme un vertige mortel. Théodora a-t-elle suggéré ce cauchemar à sa compagne, celle-ci lui a-t-elle communiqué ses terreurs ? Wise ne donne pas de réponse. Eleanor d'ailleurs désire ardemment que "quelque chose lui arrive". Elle souhaite être capturée, assimilée par la maison tentaculaire, sorte de monstrueuse Antinéa évocatrice de syncrétisme utérin, labyrinthe où il n'existe pas d'angles droits, incompréhensible volume de Klein dans lequel nous errons et qui catalyse pour nos sens d'improbables rencontres.

La maîtrise de Robert Wise réussit à traduire efficacement — et c'est là le but — ce fascinant et lucide cauchemar et fait de "The Haunting" un des plus modernes films de terreur. Les dernières images montrent Hill House après sa victoire refermée sur elle-même, immobile mais vivante Hill House veille. De nouvelles proies, de nouveaux otages ou peut-être de nouveaux élus ?

Page 116 to 118 (English translation), excerpt:

The fame of Wise, however confirmed by the success of "West Side Story", and the great fashion that striking spirits and parapsychology know nowadays, did not prevent "La Maison du Diable" [The Haunting] from making a little noticed release, to say the least, and to know a very brief exclusiveness, thus competing with "La Chute de la Maison Usher/The Fall of the House of Usher" which, in spite of its recent revival at the Studio Parnasse, was victim of a particularly inefficient exploitation.

Despite appearances, "The Haunting" is neither a real haunted house case — in the traditional sense of the word — nor one of those scams designed to scare off potential tenants as the cinema often suggested, since even the admirable "Mark Of The Vampire" submitted to these rationalist conventions. Hill House, a sinister New England home, has an unenviable reputation. For nearly a hundred years the "curse" has weighed on this horrible building, whose very appearance evokes death and slow decay. The woman for whom this house was built never lived in it and, in the park, a giant tree still bears a disturbing scar, a remnant of the accident that caused the young wife's death. Since then there has been a succession of deaths, all unusual if not suspicious, and local legend assures that the "victims" continue to populate Hill House. So far, if I dare say so, nothing but the most natural thing. The matter became more complicated when Dr. Markway, an eminent anthropologist and psychologist, decided to rent the house for the summer in order to carry out some experiments that Rhine and his colleagues would not deny. He surrounds himself with mediums — in the etymological sense of the word — that is to say, hypersensitive beings or beings in the midst of an organic or psychic mutation crisis who must allow supernatural phenomena to manifest themselves. Dr. Markway shows remarkable scientific honesty since he limits himself here to recording, without any interpretation, the occurrence and frequency of unexplained manifestations.

In "La Maison du Diable" [The Haunting] we will never know the ultimate explanation. The phenomena that were undoubtedly recorded will remain inaccessible to any rational apprehension. They are not, of course, ghosts elegantly dressed in immaculate shrouds, but simply inexplicable noises, objects moved without apparent cause and above all the resolutely atrocious impression that the House wishes to keep a living presence in it. In this case, the hypersensitive Eleanor, desperately attracted by this extraordinary residence where the high windows seem as many empty orbits, fascinating dead eyes their prey as some octopods, it is said, hypnotize their victims.

The other woman, Theodora, a beautiful brunette apparently as clairvoyant and telepathic as she is faithful to the cult of Sapho, will finally let herself be overcome by Eleanor's panicky terror. The cinema then offers us one of the purest sequences of horror when the two women taking refuge on the same bed hear the house resounding with gigantic knocks from the door of their room bending, swelling, literally distending under the monstrous pressure of the force wandering in the corridor, which we will never see and which attracts us like a deadly vertigo. Did Theodora suggest this nightmare to her companion, did the latter communicate her terrors to her? Wise gives no answer. Eleanor, moreover, longs for "something to happen to her". She wishes to be captured, assimilated by the sprawling house, a sort of monstrous Antinea evocative of uterine syncretism, a labyrinth where there are no right angles, an incomprehensible volume of Klein in which we wander and which catalyses for our senses improbable encounters.

Robert Wise's mastery succeeds in effectively translating — and this is the goal — this fascinating and lucid nightmare and makes "The Haunting" one of the most modern terror films. The last images show Hill House after its victory closed in on itself, motionless but alive Hill House stands vigil. New prey, new hostages or perhaps new chosen ones?

'Ecran 72' (France)

Feb. 1972, No. 2

Issue: Feb. 1972, No. 2

Language: French

Country: France

Content: A very comprehensive 20-page thematic dossier on Robert Wise, with many photos. Half a page, in black & white, is dedicated to The Haunting, with a commentary (interview) by Robert Wise about the film.

I can't show you the inside of the magazine without destroying the binding: it prevents from scanning the magazine flat.

Page 30 (Original French), excerpt:

Deux choses m'ont particulièrement intéressées dans la réalisation de "La maison du diable" : le développement des rapports d'amitié assez étranges et troubles entre Claire Bloom et Julie Harris — au spectateur de tirer ses propres conclusions — et l'utilisation de la bande-son comme élément dramatique du film. A aucun moment je ne montre un fantôme ou un esprit. Rien n'est matérialisé. Tout est dans l'imagination des personnages et dans la bande-son. Normalement, quand on tourne une scène, on indique oralement aux acteurs le type de son qu'on entendra dans la version finale. Et bien, pendant le tournage de "La maison du diable", pendant que l'on tournait je faisais passer le morceau de bande-son correspondant à la scène de la prise. J'ai toujours considéré le son comme un élément dramatique de première importance mais je n'avais jamais eu la possibilité de l'utiliser à fond comme je l'ai fait dans ce cas précis.

Page 30 (English translation), excerpt:

Two things particularly interested me in the making of "The Haunting": the development of the rather strange and troubled friendship between Claire Bloom and Julie Harris — it is up to the viewer to draw their own conclusions — and the use of the soundtrack as a dramatic element in the film. At no point do I show a ghost or a spirit. Nothing is materialized. It's all in the imagination of the characters and in the soundtrack. Normally, when you shoot a scene, you tell the actors verbally what kind of sound you will hear in the final version. Well, during the shooting of "The Haunting", while we were shooting, I played the soundtrack piece corresponding to the scene of the take. I've always considered sound to be a very important dramatic element, but I've never had the opportunity to use it to the fullest as I did in this case.

'Cinema' (France)

Feb. 1978, No. 201

Issue: Feb. 1978, No. 201

Language: French

Country: France

Content: A thematic dossier: Retro Satanas! Witchcraft through films. Two pages, in black & white, refer to The Haunting .

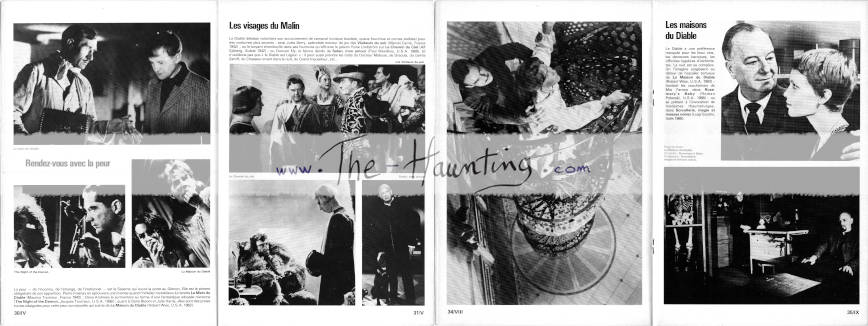

Page 30 and 34 (Original French), excerpt:

La peur — de l'inconnu, de l'étrange, de l'irrationnel — est le sésame qui ouvre la porte au Démon. Elle est le piment obligatoire de son apparition. Pierre Fresnay en éprouvera une intense quand l'hôtelier mystérieux lui tendra La Main du Diable (Maurice Tourneur, France 1942) ; Dana Andrews la surmontera au terme d'une fantastique odyssée nocturne (The Night of the Demon, Jacques Tourneur, U.S.A. 1958) ; quant à Claire Bloom et Julie Harris, elles sont des proies toutes désignées pour cette peur surnaturelle qui suinte de La Maison du Diable (Robert Wise, U.S.A. 1963).

Le Diable a une préférence marquée pour les lieux clos, les demeures baroques, les officines lugubres d'alchimistes. La nuit est sa complice. On l'imagine surgissant au détour de l'escalier tortueux de La Maison du Diable (Robert Wise, U.S.A. 1963) ; hantant les cauchemars de Mia Farrow dans Rosemary's Baby (Roman Polanski, U.S.A. 1968) ; ou se prêtant à l'invocation de modernes thaumaturges, dans Sorcellerie, magie et messes noires (Luigi Scatini, Italie 1969).

Page 30 and 34 (English translation), excerpt:

Fear — of the unknown, of the strange, of the irrational — is the sesame that opens the door to the Devil. It is the obligatory spice of its appearance. Pierre Fresnay will experience an intense one when the mysterious hotelier offers him La Main du Diable [Carnival of Sinners] (Maurice Tourneur, France 1942); Dana Andrews will overcome it at the end of a fantastic nocturnal odyssey (The Night of the Demon, Jacques Tourneur, U.S.A. 1958); as for Claire Bloom and Julie Harris, they are all prey to this supernatural fear that oozes from La Maison du Diable [The Haunting] (Robert Wise, U.S.A. 1963).

The Devil has a marked preference for enclosed spaces, baroque dwellings, the gloomy alchemists' dispensaries. The night is his accomplice. We imagine him appearing at the bend in the winding staircase of La Maison du Diable [The Haunting] (Robert Wise, U.S.A. 1963); haunting the nightmares of Mia Farrow in Rosemary's Baby (Roman Polanski, U.S.A. 1968); or lending himself to the invocation of modern miracle-workers, in Sorcery, Magic and Black Masses [Witchcraft '70] (Luigi Scatini, Italy 1969).

'Fantastic Films' (USA & UK)

USA, Sep. 1979, #10, Vol. 2, No. 4

Issue: Sep. 1979, #10, Vol. 2, No. 4

Language: English

Country: USA

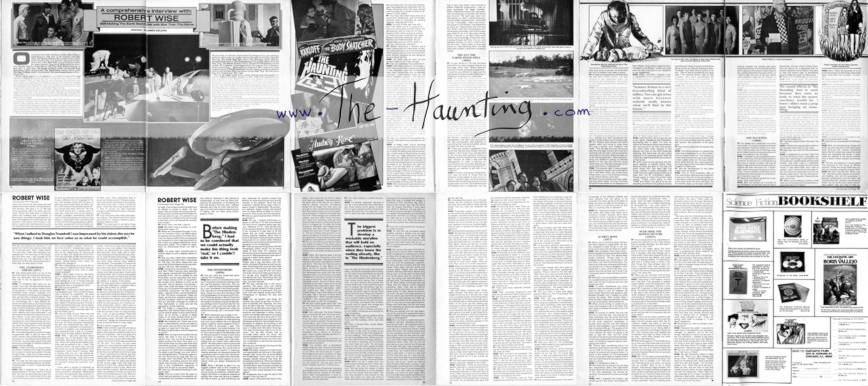

Content: Eleven full pages, in black & white, including numerous pictures. They feature a Robert Wise interview and an article by James Delson titled "A comprehensive interview with: Robert Wise."

UK, Sep. 1979, #1

Issue: Sep. 1979, #1

Language: English

Country: UK

Content: Eleven full pages, in black & white, including numerous pictures. They feature a Robert Wise interview and an article by James Delson titled "A comprehensive interview with: Robert Wise."

Page 23 & 38, very short excerpt:

Fantastic Films: You began your career as a sound effects cutter. As a result, the sound element has played an important part in your films. This is particularly true in "The Haunting", which relied heavily on its sound effects to draw the audience into the story.

Robert Wise: I decided to use a playback system on "The Haunting", the same type of system a director would use on a musical during the song or dance numbers. We had all these things that the actors had to react to, outside the door and what not. I knew I didn't want a prop man banging on something. The sound effects really had to work because they were so basic to what the actors' reactions would be.

Fantastic Films: Were all the effects worked out in advance, story-board style?

Robert Wise: Well, we worked up a number of sound effects, not the final ones we had in the picture, but very close to them. Every time we had to do a sequence that required a specific sound effect, I was able to have the actors react to something close to what you heard on the screen.

Fantastic Films: What sort of effects did you develop?

Robert Wise: Well, if you recall "The Haunting", there were no door creaks or hollow echoing footsteps. We had something outside. The ghosts, the real inhabitants of Hill House, were outside the door, so we had to create something. We made all the sounds. We made them specifically. We hired a special sound effects man, and he made the ones we used on playback during shooting. He came back afterwards and used some of those and added others. Some of the sounds were taken out of sound effects libraries, but he created the noises that chilled you.

Fantastic Films: I had bad dreams when I first saw "The Haunting".

Robert Wise: I've had some people tell me that it is the scariest movie they've ever seen.

Fantastic Films: Have you ever been terribly scared by a film?

Robert Wise: It happened to me after I saw The Cat and the Canary when I was about ten years old. I was living in a little town in the mid-west and I used to sleep with my older brother. The night I saw it, I remember running all the way home from the movie house. It was about 9:00, and I was so scared, I got in bed and just shivered under the covers for about two hours 'til my brother came home. The Cat and the Canary — I've never forgotten. Scared the bejesus out of me.

Fantastic Films: When you're making a chiller is that what you're trying to do to the audience—scare the hell out of them?

Robert Wise: Sure. That's the purpose of it, to scare the people on the screen and at the same time scare the audience, it is twofold.

Fantastic Films: What effects created for the film were you most pleased with?

Robert Wise: Well, I remember the shot where the girls are in bed. It's the first time they hear it, and the sound is kind of like a sniffing outside the door—all around the door. The feeling's like, "If there's a little crack, I can get in." I loved that. It was hand-made for the film.

Fantastic Films: When you're designing a film about a house being evil as opposed to a flesh and blood character or a moving object like an automobile, what do you look for and how do you use it?

Robert Wise: We wanted a house that basically had an evil look about it. Since the film was going to be shot in England, we looked far and wide to find the right house. There are a lot of manor houses and old places in England, but one after the other did not fit our requirements. Finally, we found one about ten miles down from Stratford-on-Avon. It was an old manor house, about two hundred years old, and it was being used as a country hotel.

Fantastic Films: What distinguished it?

Robert Wise: It had a facing of mottled stone with gothic windows and turrets.

Fantastic Films: How did you accentuate the feeling of evil?

Robert Wise: Well, we were shooting in black and white, so when we shot in the daytime, we used infra-red film. There's something about that film stock that makes the skies black and highlights the clouds. It really made the texture of the house exterior kind of awful, which worked enormously well.

Fantastic Films: The film was based on a novel called "The Haunting of Hill House" by Shirley Jackson. Since the house itself was evil, did you consider using the original title?

Robert Wise: We didn't like that title. When I say "we," that particularly means me and Nelson Gidding, who did the screenplay. It seemed cumbersome and the book had not done that well. Jackson is a marvelous writer, but her books were never tremendous sellers, they got most of their acclaim from the critics. We always felt that maybe there was a better title somewhere, and actually, she gave it to us. We had some questions about the story and her intent. Since she lived back in Vermont where her husband was a professor at Bennington, we made arrangements to fly back one weekend and meet with her. We wanted to talk about some things in her story, to get some clarifications on what her intentions were. We had lunch with her that day and during the course of it we asked her if she'd ever had any other title for it, and she said, "Well, I really hadn't. The only title I really ever seriously considered was "The Haunting of Hill House". But the other one I had thought of for a while was just "The Haunting". It was in front of us all the time, but we never saw it. She's the one who gave us that.

'Mad Movies' (France)

Jan. 1984, No. 29

Issue: Jan. 1984, No. 29

Language: French

Country: France

Content: Three quarters of a page, in black & white, with picture. The movie is reviewed by Denis Tréhin.

Page 56 (Original French)

Avec The Haunting, Robert Wise nous propose ce qu'il faut bien appeler un classique du film de maison hantée : de par son idée de départ qui doit nous permettre de suivre la visite de plusieurs personnages décidés à vérifier par eux-mêmes les phénomènes inexpliqués se déroulant dans une demeure, et de par les conséquences mortelles que va entraîner une telle expédition. Un schéma des plus classiques donc, qui fit justement de cette oeuvre le classique reconnu du genre, grâce à la force de persuasion et d'évocation qu'il génère.

C'est en Nouvelle-Angleterre que se tient Hill House, vaste demeure jamais habitée, puisque la personne pour qui elle fut construite perdit la vie dans un accident, lorsque les chevaux emballés de sa voiture vinrent se jeter contre un arbre, qui en conserva une énorme marque. D'autres personnes y périrent par la suite dans de mystérieuses circonstances, et ce sont ces victimes de la maison qui, à en croire les rumeurs, hantent dorénavant Hill House ; tel est l'historique macabre de l'endroit et la toile de fond du scénario de Nelson Gidding tiré du roman de Shirley Jackson.

Le spectateur pénètre dans les lieux comme un membre supplémentaire de la petite équipe dirigée par le Dr. Markway (Richard Johnson) et composée du neveu de l'actuelle propriétaire et de deux jeunes femmes qui possèdent une expérience dans le champ du surnaturel : Théodora (Claire Bloom), douée de pouvoirs télépathiques, et Eléanor (Julie Harris), femme hypersensible et réceptive aux forces occultes.

Durant tout le film, Wise se garde bien de donner une vision clairement définie des événements de sorte qu'il nous fait les témoins de faits étranges dont on ne peut à aucun moment dire qu'ils adviennent réellement, ou s'ils ne sont qu'hallucinations visuelles, sonores et même palpables de la part des occupants. Eléanor, de par sa sensibilité extrême, est celle qui perçoit le plus intensément l'attirance de la maison, et est le catalyseur qui laisse seulement aux autres la possibilité de deviner l'invisible. Mise à part une scène, l'au-delà se manifeste dans The Haunting par une atmosphère tenace créée par de nombreuses sources sonores : craquements, battements des fenêtres, grincement des portes, mais aussi endroits où réside un froid intense, appels de voix, pleurs de victimes invisibles ; on erre ainsi en pleine suggestion grâce au dosage calculé de tous ces effets ; c'est là du cinéma sensitif, épidermique, qui attise l'imagination du spectateur le moins sensible.

Après être entrée en contact avec Eléanor (son nom apparaît dans la poussière d'un corridor, son visage se matérialise sur une ancienne sculpture) la maison semble se déchaîner de plus en plus : une force incroyable fait se plier la porte de la chambre des deux femmes blotties sur leur lit, tandis que de formidables coups résonnent. La nuit, les plaintes de voix se font plus insistantes, et Eléanor, croyant serrer la main de sa compagne s'aperçoit que ce n'était pas à elle qu'appartenait cette main si froide !

Mais en fait, le film de Wise, s'il expose plusieurs manifestations inexpliquées relevant du surnaturel, un catalogue de phénomènes paranormaux en quelque sorte, maintient également le doute et ce, jusqu'à la fin ; l'arrivée inattendue de la femme du Dr. Markway va précipiter l'emprise (ou la névrose ?) que semble avoir la maison sur Eléanor qui, étant tombée amoureuse de Markway, va se laisser dominer par les forces qu'elle a déclenchées. On voit que tout ce qui a pu se passer est donc peut-être issu d'une vision subjective de son esprit tourmenté et qu'elle a même pu pendant un certain temps et dans des conditions propices, transmettre aux autres sa névrose.

La subtilité de The Haunting, et ce qui renforce sa crédibilité, c'est de ne point trancher, en laissant finalement planer un mystère complet sur l'origine de ce qui advient, tout en nous ayant fermement fait croire à tout ce qu'on a pu voir et ressentir. Ingénieux et dérangeant film que cette Maison du Diable qui par l'ambiguïté de son récit et par son style esthétique est à rapprocher de The Innocents.

Quant à Hill House elle-même, elle reste comme la plus réussie de toutes les demeures fantastiques vues à ce jour ; extérieurement, une vaste construction gothique impressionnante avec ses tours et ses clochers. Afin qu'il émane d'elle une sensation de menace, Wise et son équipe expérimentèrent divers éclairages qui s'avérèrent insatisfaisants ; le réalisateur eût alors l'idée d'utiliser de la pellicule infrarouge qui fit ressortir les diverses tonalités de la pierre, lui donnant ainsi un aspect s'éloignant de la pure réalité.

Page 56 (English translation)

With The Haunting, Robert Wise offers us what must be called a classic haunted house film: because of his initial idea, which should allow us to follow the visit of several characters determined to verify by themselves the unexplained phenomena taking place in a house, and because of the deadly consequences that such an expedition will entail. This is one of the most classical schemes, which has made this work the recognised classic of the genre, thanks to the persuasive and evocative power it generates.

Hill House is located in New England. It is a vast house never inhabited, since the person for whom it was built lost his life in an accident when the horses wrapped up in his carriage came to throw themselves against a tree, which left a huge mark on it. Other people later died there in mysterious circumstances, and it is these victims of the house who, rumour has it, now haunt Hill House; this is the macabre history of the place and the backdrop to Nelson Gidding's screenplay from Shirley Jackson's novel.

The spectator enters the premises as an additional member of the small team led by Dr. Markway (Richard Johnson) and composed of the current owner's nephew and two young women with experience in the field of the supernatural: Theodora (Claire Bloom), endowed with telepathic powers, and Eleanor (Julie Harris), a hypersensitive woman who is receptive to occult forces.

Throughout the film, Wise is careful not to give a clearly defined vision of the events so that he makes us witness strange facts that can never be said to actually happen, or if they are only visual, sound and even palpable hallucinations on the part of the occupants. Eleanor, because of her extreme sensitivity, is the one who perceives most intensely the attraction of the house, and is the catalyst that leaves only others the possibility of guessing the invisible. Apart from one scene, the afterlife manifests itself in The Haunting through a tenacious atmosphere created by numerous sound sources: creaking, slamming windows, squeaking doors, but also places where intense cold resides, calls of voices, cries of invisible victims; one wanders thus in full suggestion thanks to the calculated dosage of all these effects; this is sensitive, epidermal cinema, which stirs the imagination of the least sensitive spectator.

After coming into contact with Eleanor (her name appears in the dust of a corridor, her face materialises on an old sculpture) the house seems to go wilder and wilder: an incredible force makes the door of the two women's room bend open, huddled on their bed, while formidable blows resound. At night, the complaints of voices become more insistent, and Eleanor, believing she is shaking hands with her companion, realizes that it was not her who owned this cold hand!

But in fact, Wise's film, while exposing several unexplained manifestations of the supernatural, a catalogue of paranormal phenomena of sorts, also maintains doubt right up to the end; the unexpected arrival of Dr. Markway's wife will precipitate the hold (or neurosis?) that the house seems to have on Eleanor who, having fallen in love with Markway, will let herself be dominated by the forces she has unleashed. We can see that everything that may have happened may have been the result of a subjective vision of her tormented mind and that she was even able, for a certain time and under favourable conditions, to transmit her neurosis to others.

The subtlety of The Haunting, and what reinforces its credibility, is that it doesn't make any statement, finally leaving a complete mystery as to the origin of what happens, while at the same time having made us firmly believe in everything we have seen and felt. An ingenious and disturbing film, this Maison du Diable, which by the ambiguity of its narrative and its aesthetic style is to be compared to The Innocents.

As for Hill House itself, it remains as the most successful of all the fantastic residences seen to date; externally, a vast and impressive Gothic building with its towers and bell towers. In order to create a sense of threat, Wise and his team experimented with various lighting techniques which proved unsatisfactory, and the director had the idea of using infrared film which brought out the various tones of the stone, giving it an appearance far removed from pure reality.

Connoisseurs will notice that this is a really nice promotional picture. The surroundings of the house changed a lot since this picture was taken.

'Fangoria' (USA)

May 1982, #19

Issue: May 1982, #19

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: Five full pages, in black & white, including numerous pictures. They feature a Robert Wise interview and an article by Al Taylor, Doug Finch and Bruce Benderson titled "Val Lewton's Cats"

Page 40, very short excerpt:

Fang: What would you consider the Lewton formula for building a horror?

Wise: One of the greatest things that Lewton played on, or tried to play on in most of his films, was people's fear of the unknown. He felt that this was the greatest fear that we have. If we don't know about something, we have concern and fear. He played on that and worked toward building everything he could towards a response to the fear of the unknown.

And of course, he would want to time how effects would go. He was very careful about his continuity, how he built the scenes, how he built the continuity of the piece, to be sure there were not too many long passages without something happening. Something to get the audience, something to make them react, something to bring them uptight.

Fang: Who would you consider your mentors in the early RKO days?

Wise: T.K. Wood, the sound effects editor, who not only taught me about sound effects editing, but about life in the studio and life generally- He was a lovely, quiet, fun man.

Another was Billy Hamilton, the editor I started with. Billy was absolutely marvelous to me. He taught me as much as I know about editing. He was a master editor himself.

Of course, Orson Welles was a mentor too—a tremendous talent. The experience of working with him was quite unusual, quite stimulating, quite exciting, quite maddening. But overall, just tremendous.

There was also Richard Wallace. He was a very lovely man and a good director in those days. I can't give you a list of all the films he did. Most of them kind of middle ground pictures—no great world-renowned titles that you would remember. But a good, more than competent director and a lovely man.

Of course, my greatest mentor was Val Lewton, my first producer. Val taught me so much about filmmaking; about the importance of detail, the tempo of the script, writing—just everything; care, attention and love given to all aspects of the film. I shall always be thankful to him.

May 1985, #44

Issue: May 1985, #44

Language: English

Country: USA

Content: Five full pages, in black & white, including numerous pictures. They feature a Robert Wise interview and an article by John Gallagher titled "Wise Fantastica - Tutored in horror and fantasy by the great Val Lewton, successful mainstream director Robert Wise has often returned to his fantastic film roots."

Page 60, very short excerpt:

Fangoria: You were very influenced by the Lewton thrillers when you directed "The Haunting" 20 years later.